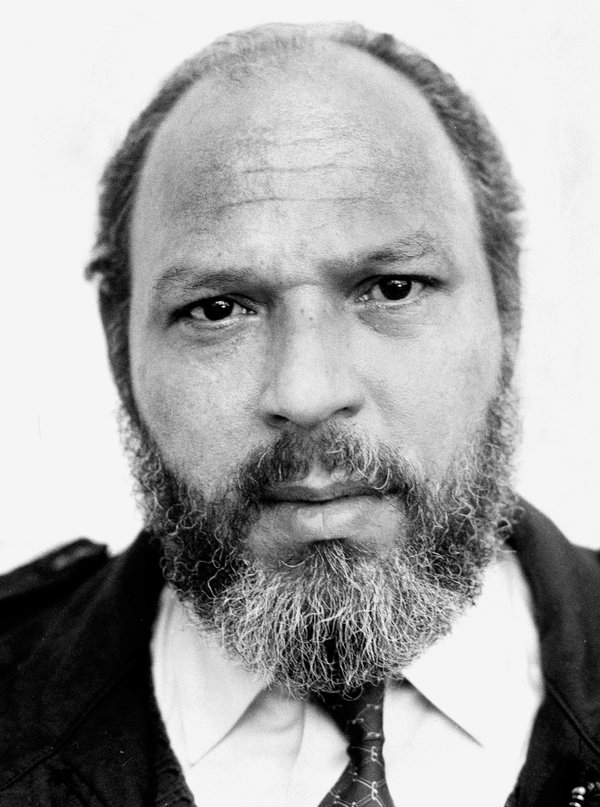

Colin Kaepernick, August Wilson, and the Denial of Black Freedom

Living in the United States of America means receiving an abundance of messaging about freedom, a concept often touted as the pillar of American national identity. Look no further than the National Anthem or the Pledge of Allegiance, which both solidify commitments to “the land of the free” and to “liberty and justice for all,” respectively. These messages, though, have been perpetuated throughout America’s history without simultaneous inquiry into the actual definition of freedom. Widespread interrogation of freedom might be avoided by Americans because it is difficult to quantify and thus deconstruct the term, but also because America’s regurgitation of freedom has framed it as an inherent component of the country and thus unworthy of close inspection. But, without examining freedom, one can ignore society’s many ills; a plethora of American issues contain an underlying theme of freedom and its conflicting nature. One such conversation is the black American struggle. Freedom has remained prominent in racial issues throughout American history, frequently taking on literal manifestations (enslavement, emancipation, segregation).

For much, if not all, of black history in America, the societal expectation of freedom has not been granted to black people. This exclusionary intersection of freedom and blackness is exemplified through August Wilson’s Gem of the Ocean and Colin Kaepernick’s protest, two vastly different, yet connected, elements of expression. Despite the massive time difference between Gem of the Ocean, a play set in 1904 Pittsburgh, and Kaepernick’s contemporary protests, both showcase a similar understanding of the relationship between blackness and freedom in America.

In Gem of the Ocean, Wilson explores freedom, among various other themes, through the lens of black life after the Emancipation Proclamation. Several characters experienced slavery first-hand and other younger characters were born into emancipation, a distinction that produces different perspectives about what it means to be free and informs the characters’ expectations of freedom. Much of the same inquiry substantiates Colin Kaepernick’s modern-day protests. During the 2016 NFL season, quarterback Kaepernick decided to kneel instead of stand while the national anthem was played before his games. Similar to the characters in Gem of the Ocean, Kaepernick’s decision to kneel allows him to question what it means to be free and black in America.

The country’s tense response to freedom and blackness emerges early in Gem of the Ocean. Character Solly receives a letter from Eliza, his sister in Alabama, who writes that “the people are having a hard time with freedom,” referring to both black and white people’s trouble with emancipation (Wilson 15). Eliza says that the white people in Alabama went “crazy” by beating, killing, and intimidating black people, making it difficult for black people to leave the area (Wilson 15). Additionally, within the Pittsburgh community, black constable Caesar uses his authority to brutalize black people, doing so in a way that suggests that he might excel at “keeping…niggers in line” on a slave plantation (Wilson 14). He approaches his job from a place of respectability politics, declaring that “It’s Abraham Lincoln’s fault” for the chaos in Pittsburgh, as “you try and do something nice for niggers and it’ll backfire on you every time” (Wilson 34).

The presence of violence in spite of emancipation is a constant theme in Gem of the Ocean that also extends to Kaepernick’s actions on freedom. Explaining the motivation behind his protest, Kaepernick told news media that “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color. … There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder” (Wyche). Kaepernick’s quote connects state-sanctioned violence to the country’s oppressive lack of freedom. His stance aligns with Gem of the Ocean, as the play forces readers to question whether freedom has been truly achieved if violence against black bodies still exists. Kaepernick, nearly in direct response to that question, decided to disregard pride in American freedom because he had observed the continued existence of societal violence towards black bodies.

Questions about freedom are also raised by Gem of the Ocean through many instances of direct dialogue. Solly says that, “You got to fight to make [freedom] mean something…What good is freedom if you can’t do nothing with it?” (Wilson 28). Later in the play, Eli claims that the fight for freedom is “a war and you always on the battlefield,” to which Solly says, “The field of battle is always bloody. … It can’t be no other way” (Wilson 59). Despite emancipation and the country’s commitment to “freedom for all,” black people must still fight for their freedom – another example of freedom and blackness’ convoluted relationship. This fight for freedom is visible throughout the entire history of the black struggle in America, as black attempts for liberation have frequently been met with war-like white resistance. Thus, how can freedom really exist for black people if it requires constant battle to acquire said freedom? The inconvenience, yet necessity, of bloody battle can be seen in Kaepernick’s protest. Engaging in the fight means personal loss, but Kaepernick stated that “I have to stand up for people that are oppressed. … If they take football away, my endorsements from me, I know that I stood up for what is right” (Wyche). In his case, Kaepernick’s bloodshed (his sport and endorsements) is not literal. Much like Solly’s designation of the fight for freedom as bloody, Kaepernick understands the damaging byproduct of his actions against oppression.

Exploring the relationship between freedom and blackness allows for an exploration of the black experience in America. It is difficult to understand blackness without looking at its relationship to freedom, as so much of black identity is formed out of the country’s consistent denial of black freedom. Despite understanding the historical legacy of black denial of freedom, it is still shocking to see such vivid parallels between a 1904 play and a 2016 protest. The different, yet connected, work of Wilson and Kaepernick vocalize the problematic and exclusionary nature of American freedom for the black community.

Exploring the relationship between freedom and blackness allows for an exploration of the black experience in America. It is difficult to understand blackness without looking at its relationship to freedom, as so much of black identity is formed out of the country’s consistent denial of black freedom. Despite understanding the historical legacy of black denial of freedom, it is still shocking to see such vivid parallels between a 1904 play and a 2016 protest. The different, yet connected, work of Wilson and Kaepernick vocalize the problematic and exclusionary nature of American freedom for the black community.

In Gem of the Ocean, Solly burns down the mill to protest his limited freedom. That decision ends with him shot dead before he can flee Pittsburgh. In 2016, Kaepernick decided to kneel in protest of systemic oppression. As a response, he was ostracized from the NFL.

I believe that both of the responses reflect a larger national commitment to maintaining a denial of black freedom in America. After all, the punishments of Solly and Kaepernick reinforce their idea that their bodies truly are not free – otherwise, there’d be no reason for punishment. But, growing up in America means that one also grows up with an instilled image of America’s “commitment” to granting freedom for all.

But, considering the exclusionary and violent repercussions of freedom’s illusion, when will America actualize the goal of freedom for all? At times, I wonder if freedom and blackness will always remain conflicted – after all, has the status of black freedom substantially changed during the last 112 years of American history?

—

Works Cited:

Wilson, August. Gem of the Ocean. Samuel French, 2015.

Wyche, Steve. “Colin Kaepernick explains why he sat during national anthem.” NFL.com, 27 Aug. 2016, www.nfl.com/news/story/0ap3000000691077/article/colin-kaepernick-explains-why-he-sat-during-national-anthem. Accessed 27 Sept. 2017.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post